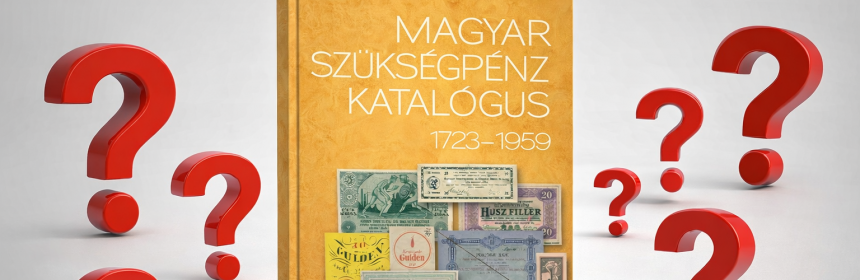

New catalog about Hungarian emergency notes: Ifj. Adamovszky István és Feczkó Csaba – Magyar szükségpénz katalógus

In December 2025, the book titled Catalogue of Hungarian Emergency Money by István Adamovszky Jr. and Csaba Feczkó was published. Upon taking it in hand and leafing through it, the book caused disappointment for many collectors. Based on feedback from collectors, as well as an objective examination of the book’s content, it is easy to conclude that its contents are detrimental to collectors, to collecting as a practice, and to the development of Hungarian numismatics.

The following issues arise in connection with the publication:

1. Presenting forgeries as genuine originals.

The book contains various modern forgeries in the dozens, yet no indication whatsoever is given regarding their authenticity—while market prices are nevertheless provided. Although there are some examples whose authenticity may be doubtful and open to debate, in most cases banknotes are presented as genuine that are recognizably fake even to a beginner collector.

* Forgeries produced using modern printing techniques, modern graphics and modern typefaces.

Anyone who is at least somewhat familiar with the world of paper money knows what kind of visual design is appropriate for banknotes of a given era. It is obvious that in the 1920s, stock photos downloaded from the internet were not used, nor the font set of MS Word, and emergency money was certainly not produced with a color laser printer.

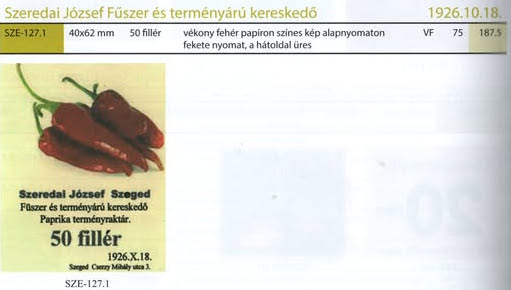

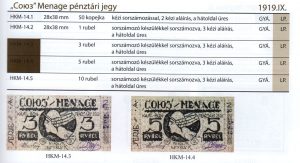

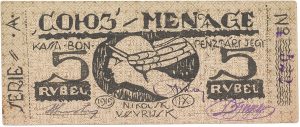

1. example:

A stock photo of hot peppers, as well as modern typefaces, were used:

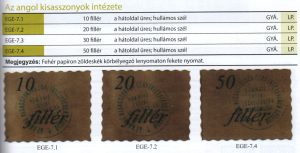

2. example:

The italic version of the Times New Roman typeface appears on the forgery.

* Forgeries of identical design made with ‘potato printing,’ handwriting, or typewriter.

In some forgeries, even though the place of issue differs, the time gap spans several decades, or they may belong to different monetary systems, the same elements are repeated. In the case of hand-made (stamped or drawn) or typewritten copies that were later multiplied, it is impossible for identical appearances to occur at different times and locations.

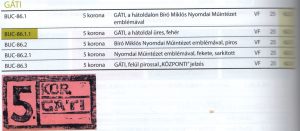

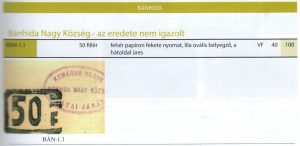

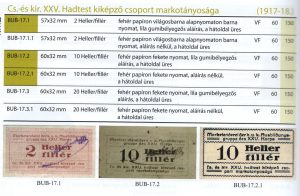

3. example:

As a positive note, it can be mentioned that in some places the remark ‘authenticity not verified’ appears.

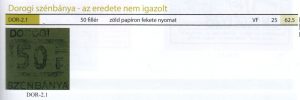

4. example

Forgeries hand-drawn in the same style, then reproduced in identical colors.

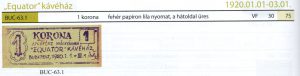

5. example

Not only do the production style and method of reproduction repeat, but in some forgeries that are far apart in time and place, the paper type and perforation are also identical.

* Photocopied and otherwise reproduced forgeries.

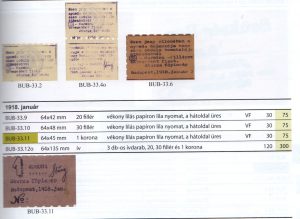

6. example

1st image: 2 fillér, original example.

2nd image: 10 fillér, photocopy of the 10 fillér held at the Hungarian National Museum.

3rd image: 10 fillér, primitive copy (previously sold by the Darabanth auction house).

In the case of the 10 fillér, the original example is not described (similar to the 2 fillér, but with a greenish underprint); instead, the copies are presented as originals.”

2. Entrance tickets, membership certificates, donation vouchers, etc., mistakenly presented as emergency money.

3. The catalog ignores publications and releases from the past decades.

The catalog was essentially compiled based on images of emergency money (as well as tickets, donation vouchers, etc.) known to the authors. Largely, they ignored both Hungarian and foreign-language numismatic literature, as well as publications in numismatic journals. As a result, the book is outdated, incomplete, and erroneous in many places.

From a numismatic perspective, the catalog represents an absurd step backward in several respects, as in many cases—due to a lack of knowledge—it oversimplifies topics that had previously been treated in detail, reducing them to a level several decades old.

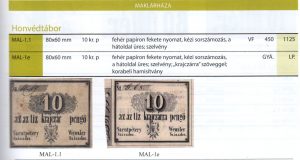

9. example:

Incorrectly attributed to Maklárháza.

Its source is Béla Ambrus’s 1977 book Hungary’s Emergency Paper Money from 1723 to 1914.

In fact, it was issued in Pétervárad, not Maklárháza, and its history is relatively well documented.

Sources:

Bocz Péter: Péterváradi szükségpénzek 1849, Az Érem, 1992

Kuscsik Péter: Magyarország állami és helyi papírpénzei 1811–1892, 2022

4. Images with incorrect proportions.

The images in the book are randomly stretched or compressed in width, meaning they do not preserve the true width-to-height ratio. This problem runs throughout the entire book: in most cases it is barely noticeable, but on numerous occasions the distortion is so significant that the depicted banknote does not actually exist in that form. For example, a rectangular banknote is shown as square. This, in turn, creates the potential for misleading readers.

10. example:

Compressed:

In fact:

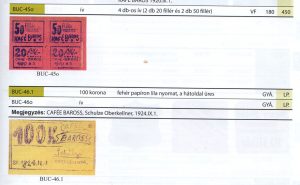

11. example:

Stretched (the circular punch became oval):

Summary:

The greatest problem with the publication is the presentation of forgeries as genuine items, as well as its indiscriminate cataloging of various tickets and slips as emergency money. One could argue that the authors cannot know everything; however, in many cases these forgeries were already known to collectors years earlier, had been discussed in publications, and were even treated as forgeries in the numismatic literature. Similarly, it is difficult to understand why items that are clearly not emergency money were included en masse in the book.

If the inclusion of forgeries was intentional, this represents a serious problem; if it was unintentional and merely the result of insufficient verification, it points to even more serious shortcomings and amateurishness.

Another notable feature is that, although in many cases it is recognizable where the images came from and from whom, the book does not provide source citations or acknowledgments. Likewise, the bibliography of sources used is missing, even though in several cases it is clearly identifiable—particularly based on the works of Béla Ambrus—what sources the information can be traced back to.

Overall, the book may be harmful primarily to beginner collectors and those interested in numismatics. It presents such a volume of incorrect information that it can easily create a distorted view of what should be considered emergency money and what counts as a genuine item.

At the same time, the book’s merits and usefulness must be acknowledged, though they should be understood in context. It contains a large number of images, and in several cases presents emergency money that had not previously appeared in print. The pricing information is generally indicative and practically useful, making the publication particularly valuable for dealers.

The aim of my critique has been to contribute, in general, to raising the standard of Hungarian numismatic literature. Hopefully, in any future edition, the shortcomings and errors detailed above will be corrected.

– KP

This translation from the Hungarian version was produced using AI.

The use of the images in this writing does not infringe copyright, as they are employed solely for illustrative and educational purposes. The images are not presented as independent content but to support, analyze, and critically examine the professional statements made in the text.

The purpose of their use is non-commercial, aimed at numismatic education, professional critique, and informing collectors.

In all cases, the images help illustrate the phenomena under discussion—such as authenticity and the identification of forgeries—and are therefore closely connected to the content of the text.

Moreover, the scope of the images used is limited to what is necessary, and they do not replace the original publication nor diminish its market value. Accordingly, the presentation of the images falls within the framework of fair use and professional citation practices, for educational and informational purposes.